Executive (Dis)Order: Trump’s Unprecedented Use of Executive Orders and How States Are Fighting Back

During President Trump’s second term in office, the use of executive orders has skyrocketed. New analysis from States United shows that from Jan. 20, 2025, to Jan. 12, 2026, President Trump issued 228 executive orders. The volume and pace of Trump’s executive orders far exceed every other president in contemporary history.

One year into Trump’s second term, this new data highlights a governing style that relies heavily on unilateral action—even at a time when the president’s party controls both chambers of Congress. The analysis also shows how Trump’s use of executive orders has repeatedly overstepped the limits of presidential authority, forcing states and other parties to push back, resulting in courts invalidating several of his most prominent initiatives.

While executive orders are a powerful tool to guide the management of the federal government that have been deployed by presidents of both parties, they have clear limits. Executive orders cannot conflict with laws passed by Congress, and they cannot infringe on constitutional rights. They are not statutes and issuing them is not a substitute for the actions of Congress. They are, in short, written directives on how the executive branch seeks to apply and enforce current laws and regulations.

States are directly impacted by the president’s executive orders, on topics including law enforcement, elections, and birthright citizenship, and they continue to play a leading role in challenging the administration’s actions in court. And the American people aren’t on board either. States United polling shows that Americans would much prefer the president work with Congress to pass legislation than pursue his agenda through executive fiat.

This report highlights the pattern of unilateral executive action that characterizes the second Trump administration by examining the president’s use of executive orders through Jan. 12, 2026. (The analysis focuses exclusively on executive orders and does not include other presidential actions like memorandum and proclamations.)

- From Jan. 20, 2025, through Jan. 12, 2026, Trump issued 228 executive orders.

- The volume and pace of Trump’s executive orders exceed every other president in contemporary history.

- Courts have invalidated several of Trump’s most prominent initiatives issued by executive order—and many others are in ongoing litigation.

- States are directly impacted by the president’s executive orders—and they play a leading role in challenging the administration’s actions in court.

- States United polling shows that Americans would much prefer the president work with Congress to pass legislation than change policy with executive orders.

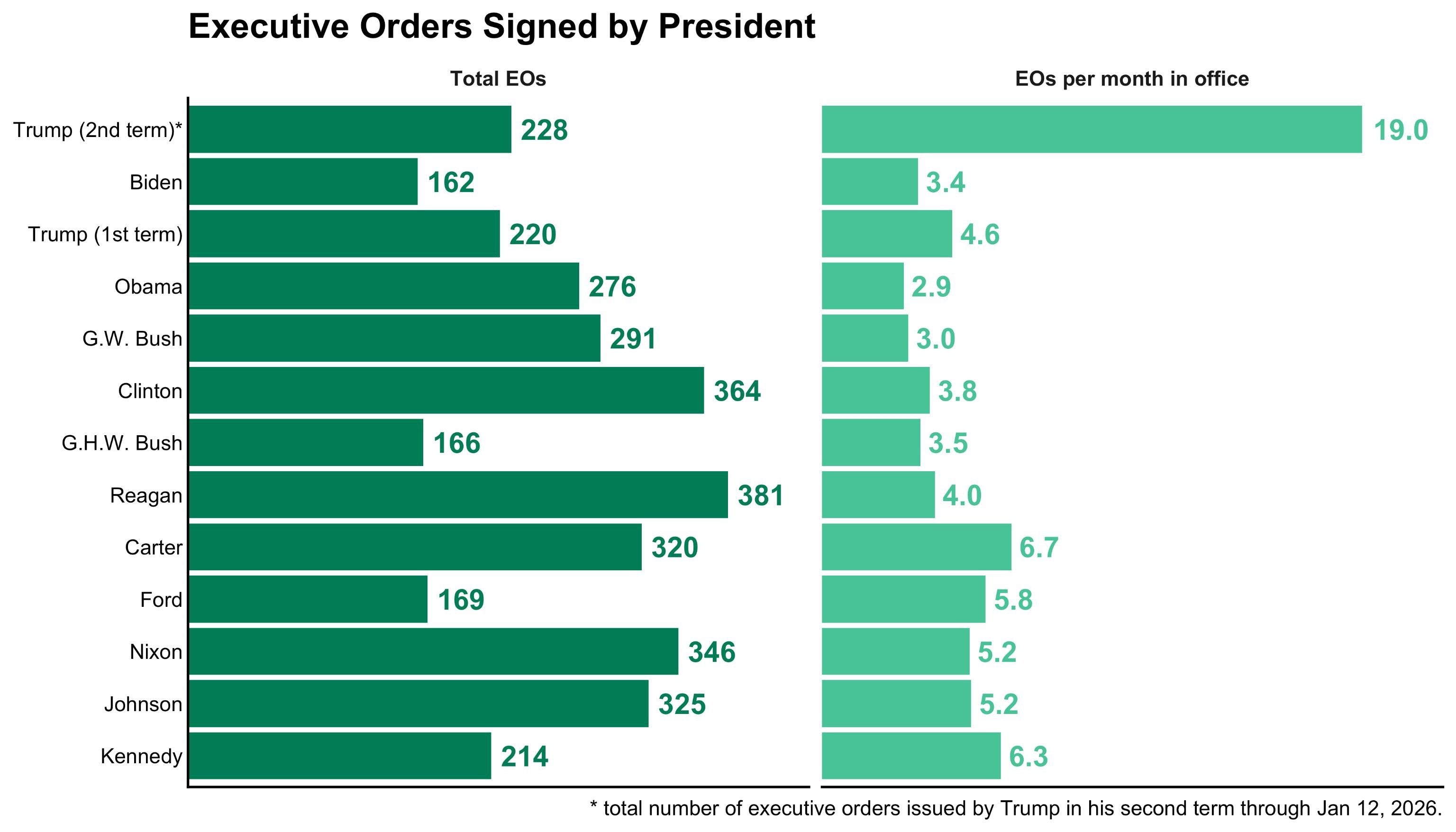

Since returning to office in January 2025, President Trump has issued 228 executive orders through Jan. 12, 2026. The pace and volume of the administration’s use of executive orders is unprecedented in contemporary American history.

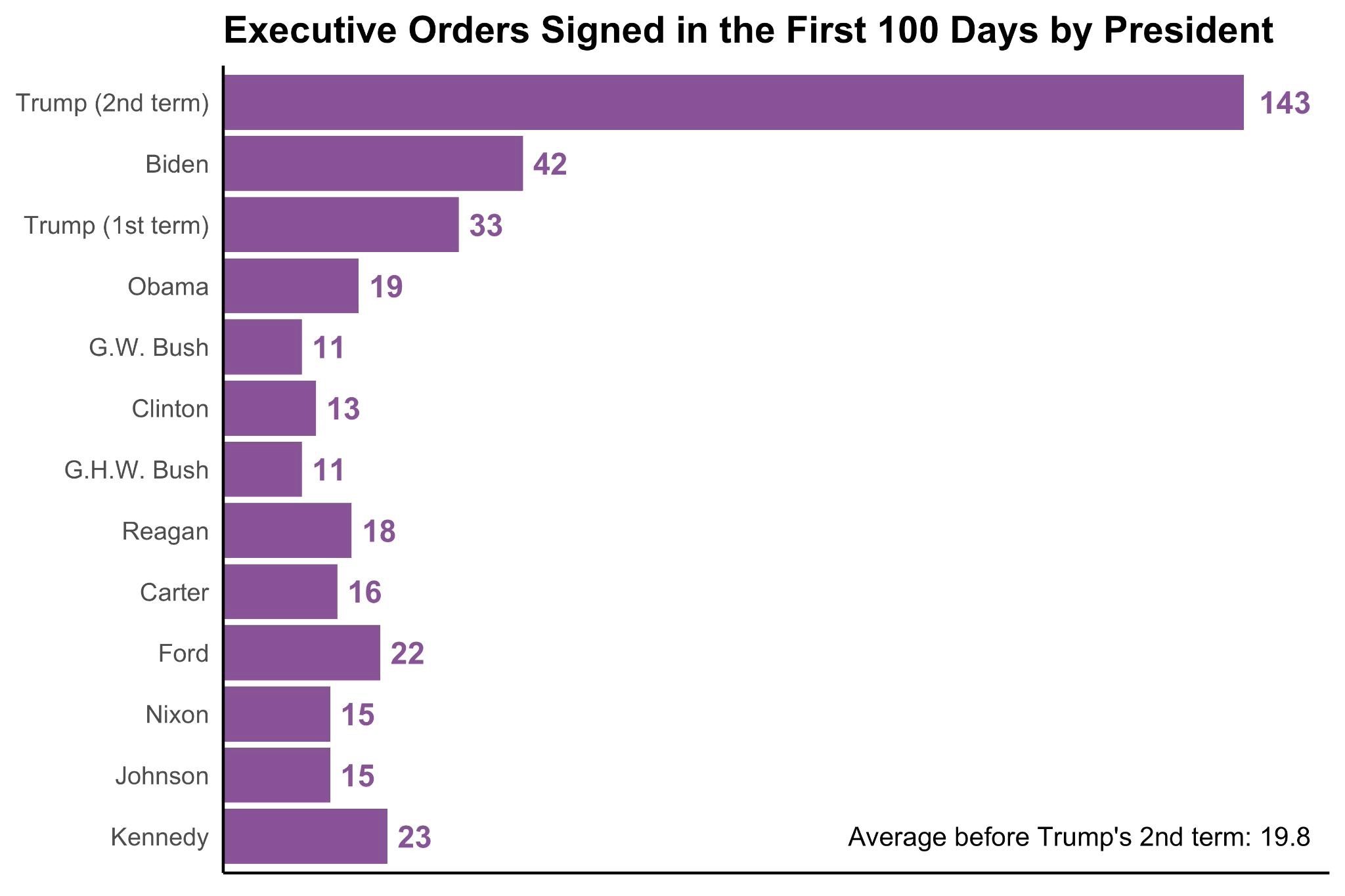

Presidents from John F. Kennedy to Joe Biden issued an average of 19.8 executive orders in their first 100 days. Most of Trump’s predecessors, from Kennedy to Barack Obama, fell within a relatively narrow band of 12 to 23 orders in their first 100 days. Biden issued 42 executive orders in his first 100 days, which itself was a record at the time among recent presidents.

In this context, Trump’s second term use of executive orders stands out dramatically: He issued 143 orders in his first 100 days. That is 7.2 times the historical average and more than 3.4 times the number used by Biden.

Source: U.S. Federal Register list of Executive Orders

Trump’s frequent use of executive orders in his second term did not stop after the first 100 days, either. In his first year, he has already surpassed or nearly matched the number of executive orders that his predecessors issued over their entire presidencies. Trump’s flood of executive orders in his second term marks a sharp break with history.

Source: U.S. Federal Register list of Executive Orders

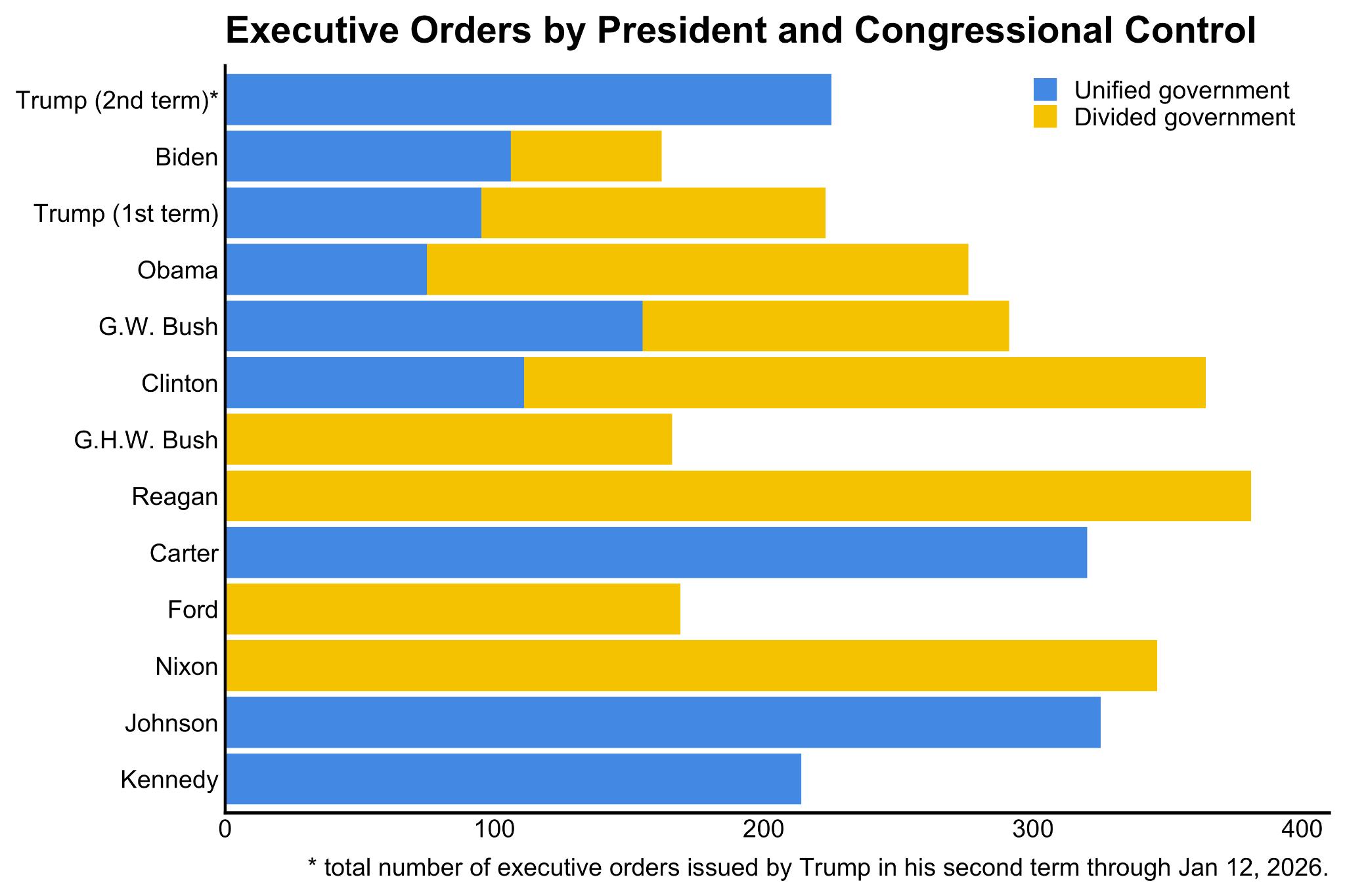

Traditionally, presidents have turned to executive orders when one or both chambers of Congress is controlled by an opposing party. Under a divided government, executive orders can be a way that presidents try to navigate gridlock and legislative opposition.

President Clinton, for example, issued more than twice as many executive orders when Congress was under divided control as he did when Democrats held both chambers. Both Obama and Trump, during his first term, followed the same pattern of issuing more executive orders when facing divided government in the legislative branch. (There are exceptions to this trend as well; Presidents Carter and Johnson issued hundreds of executive orders over the course of their full presidencies under unified government.)

In the first year of his second term, however, Trump has relied on unilateral action to an extraordinary degree, despite holding unified control of both chambers of Congress. His 228 executive orders covered in this analysis have been issued while Republicans control both the House and Senate. While the narrowly divided chambers can contribute to legislative gridlock, Trump’s frequent reliance on executive orders suggests a preference to draw on presidential power rather than utilize the legislative process.

Source: U.S. Federal Register list of Executive Orders

Trump’s executive orders have imposed sweeping changes that affect state governments and their citizens, including orders that intrude on traditional areas of state authority like administering elections and deploying the National Guard. These orders have sparked an extraordinary wave of litigation between states and the administration.

During Trump’s first term, 246 total court cases challenged his administration’s use of executive power (actions that included executive orders as well as other actions like regulations and agency memoranda). The administration prevailed in only 22% of those cases, losing nearly four out of five times.

Overturned executive orders from Trump’s first term include the first travel ban against seven predominantly Muslim countries (EO 13769), which was met with several lawsuits, blocked by the courts, and eventually replaced by new travel bans; Trump’s attempt to condition federal grants on “sanctuary” policies (EO 13768), which was ruled unconstitutional by the Ninth Circuit; his refugee-consent order (EO 13888) allowing state and local authorities to turn away refugees, which was blocked by a federal court; and an order limiting contractor diversity training (EO 13950), which was also blocked by a federal court.

States United research shows that Trump’s second term follows a similar pattern of court challenges. At least 33 of the president’s 228 executive orders are already facing federal court challenges. While many of these cases continue to move through the courts, some of his most controversial executive orders have been blocked, as highlighted below, though many of these cases remain pending on appeal.

Below we provide some prominent examples of executive orders from 2025 that have impacted state and local governments—and related legal challenges brought by state leaders to push back:

- Executive Order 14160, which attempts to end birthright citizenship for U.S.-born children of certain immigrants. Twenty-two states and Washington, D.C. filed lawsuits arguing that the order violates the 14th Amendment’s Citizenship Clause. Several federal judges have agreed and the order has already been blocked by multiple federal courts. On Dec. 5, 2025, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments in one of the cases challenging the order’s constitutionality. As of publication, oral argument has not yet been scheduled, but is likely to occur in the spring, with a decision anticipated by June or July.

- Executive Order 14248, which attempts to assert control over state and local election practices. The order, among other things, directs the Elections Assistance Commission to take steps to require documentary proof of citizenship for voter registration, requires states to reject absentee and mail-in ballots received after Election Day, and threatens to withhold federal funding for states that do not comply with the order. The order has been challenged in multiple lawsuits, including by a coalition of nineteen states in California v. Trump, No. 25-cv-10810 (D. Mass.), and in a separate action brought by Washington and Oregon, Washington v. Trump, 25-cv-00602 (W.D. Wash.). The plaintiff states argue that the order unlawfully claims federal control over election administration, an area that the Constitution reserves for the states and Congress, by violating the Elections Clause and separation of powers principles. On June 13, 2025, a federal court in California v. Trump temporarily blocked key provisions of the order from taking effect while the case continues, a ruling the administration has appealed to the First Circuit. On Jan. 9, 2026 a federal court in Washington v. Trump permanently blocked several of the order’s core provisions, including provisions that would require documentary proof of citizenship to register to vote and provisions that would withhold federal funding from states that accept postmarked mail ballots received after Election Day.

- Executive Orders 14252, 14333, and 14339, which direct federal agencies to exert expanded authority over law-enforcement operations in Washington, D.C., in response to the president’s declaration of a “crime emergency.” The orders require increased enforcement of certain criminal laws in the District, particularly those relating to immigration enforcement, and the mobilization of a “specialized” unit within the D.C. National Guard dedicated to ensuring “public safety” and deputized “to enforce Federal law” in the capital. A related presidential memorandum further directed the secretary of defense to coordinate with governors to deploy members of their National Guard forces to the District. National Guard units from at least 11 states have since been deployed to D.C. On Sept. 4, D.C. Attorney General Brian Schwalb filed a lawsuit challenging the president’s authority to deploy National Guard troops to the District, including directives made under Executive Order 14339. The suit alleges that the administration’s deployment of National Guard troops violates D.C.’s autonomy under the Home Rule Act; that enlisting National Guard, pursuant to Executive Order 14339, for domestic law enforcement violates the Administrative Procedures Act and the Posse Comitatus Act; and that the administration’s actions in D.C. exceed longstanding limits on executive power, including separation of powers principles and the Take Care Clause. Twenty-two states filed an amicus brief supporting the District’s position. On Nov. 20, 2025, a federal court granted D.C.’s request for immediate relief and temporarily blocked the Department of Defense from deploying or requesting deployment of National Guard members to the District. On Dec. 17, 2025, the D.C. Circuit, in a 3-0 decision, stayed the lower court’s order, permitting the deployment of National Guard forces in D.C. pending appeal.

- Executive Orders 14193, 14194, 14195, 14257, and 14266, which impose new or expanded tariffs on imports, including on products imported from Canada, Mexico, and China under the authority of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). A coalition of 12 states, led by the Oregon Department of Justice, is challenging these orders, arguing that they exceed presidential authority because the Constitution gives Congress—not the president—the power to set tariffs, and IEEPA does not authorize tariffs of this kind. The states also contend that these tariffs effectively raise taxes on Americans and circumvent the legislative process. On May 28, 2025, the U.S. Court of International Trade agreed with the states, granting summary judgment and permanently blocking enforcement of the tariffs. The Federal Circuit affirmed the decision. The Supreme Court heard oral arguments in this case in November.

Recent polls show that many Americans are uneasy with how Trump is governing, particularly in his use of executive power.

A Pew Research Center survey from October 2025 found that nearly seven in 10 Americans (69%) think Trump is trying to exercise more power than previous presidents, while only about one in five (21%) believe he’s staying within normal limits. More than half (51%) also said Trump is relying too heavily on executive orders.

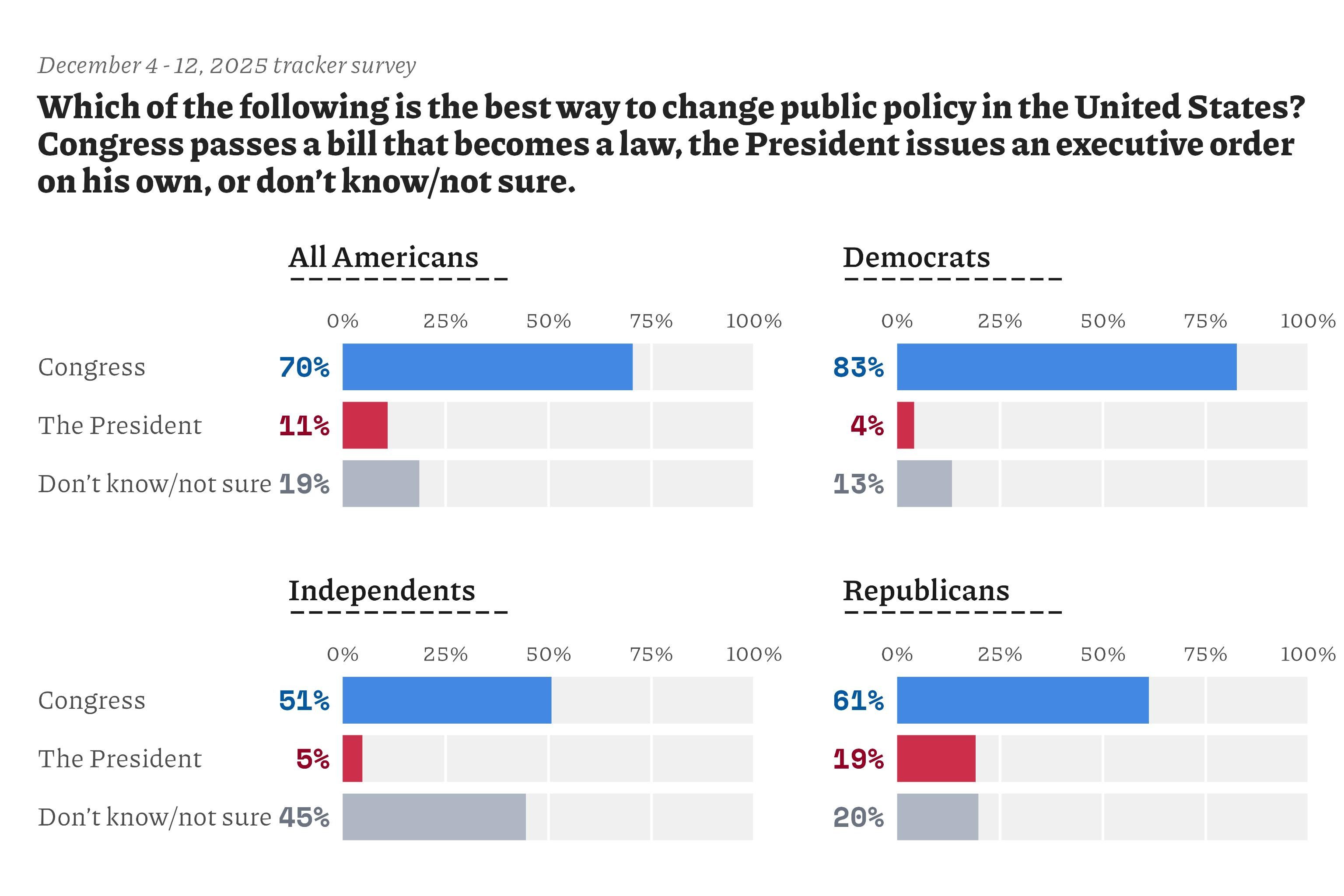

Most Americans want checks and balances preserved and object to Trump’s unilateral approach to advancing his agenda. States United polling from December 2025 found that 70% of Americans believe the best way for public policy to change is by Congress passing a bill that becomes a law.

President Trump’s use of executive orders is unprecedented. An executive order is one administrative tool that U.S. presidents use to guide policy priorities, but Trump’s use of them exemplifies a unilateral approach to governance that routinely side-steps Congress and results in federal overreach that likely exceeds the boundaries of presidential authority.

States have been directly impacted by the president’s executive orders across a range of policy areas—from public health funding to law enforcement—and they have successfully challenged many of the orders in court.

Americans ultimately prefer the president to adhere to the separation of powers and work with Congress to pass legislation that becomes law, rather than attempt to assert new policy approaches through unilateral executive action.

This analysis is based on presidential executive orders posted on the Federal Register and the White House’s Executive Order announcement page. The dataset includes every executive order issued from Kennedy through Trump’s current term (as of Jan. 12, 2026, 12 p.m. EST), categorized by the political alignment of government control at the time.

The number of executive orders currently facing federal court challenges was obtained using the Just Security Litigation Tracker: Legal Challenges to the Trump Administration. This tracker compiles all known cases challenging executive actions and identifies which specific executive order is being challenged.

Polling data are taken from a States United survey based on 1,515 interviews conducted on the internet of U.S. adults. Participants were drawn from YouGov’s online panel and were interviewed from Dec. 4–12, 2025. Respondents were selected to be representative of American adults. Responses were additionally weighted to match population characteristics with respect to gender, age, race/ethnicity, education of registered voters, and U.S. Census region based on voter registration lists, the U.S. Census American Community Survey, and the U.S. Census Current Population Survey, as well as 2020 presidential vote. The margin of error for this survey is approximately ± 2.8 percentage points, though it is larger for the analysis of partisan subgroups described above. Therefore, sample estimates should differ from their expected value by less than the margin of error in 95% of all samples. This figure does not reflect non-sampling errors, including potential selection bias in panel participation or measurement error. In keeping with best research practices, we classify independent voters who reported “leaning” toward either the Democratic or Republican parties as partisans. Therefore, we define “independents” as those respondents who professed no partisan attachments whatsoever.