Tracking Attitudes About Voters’ Confidence in Elections

In This Resource

Following the 2024 election, Americans expressed a modest increase in confidence in the integrity of U.S. elections.

The slight overall change in confidence reflects substantial shifts in partisan attitudes: Following Trump’s victory, Democrats became moderately less confident about the integrity of our elections, while Republicans became substantially more confident. New national polling from States United further reveals that these shifts endured through the first quarter of 2025.

The findings offer compelling insights into how voters form their perceptions of election integrity. As we discuss below, the confidence shifts that followed the 2024 election can be attributed not only to common post-election effects, but also to shifts in how public officials speak about our election system and shape voter attitudes.

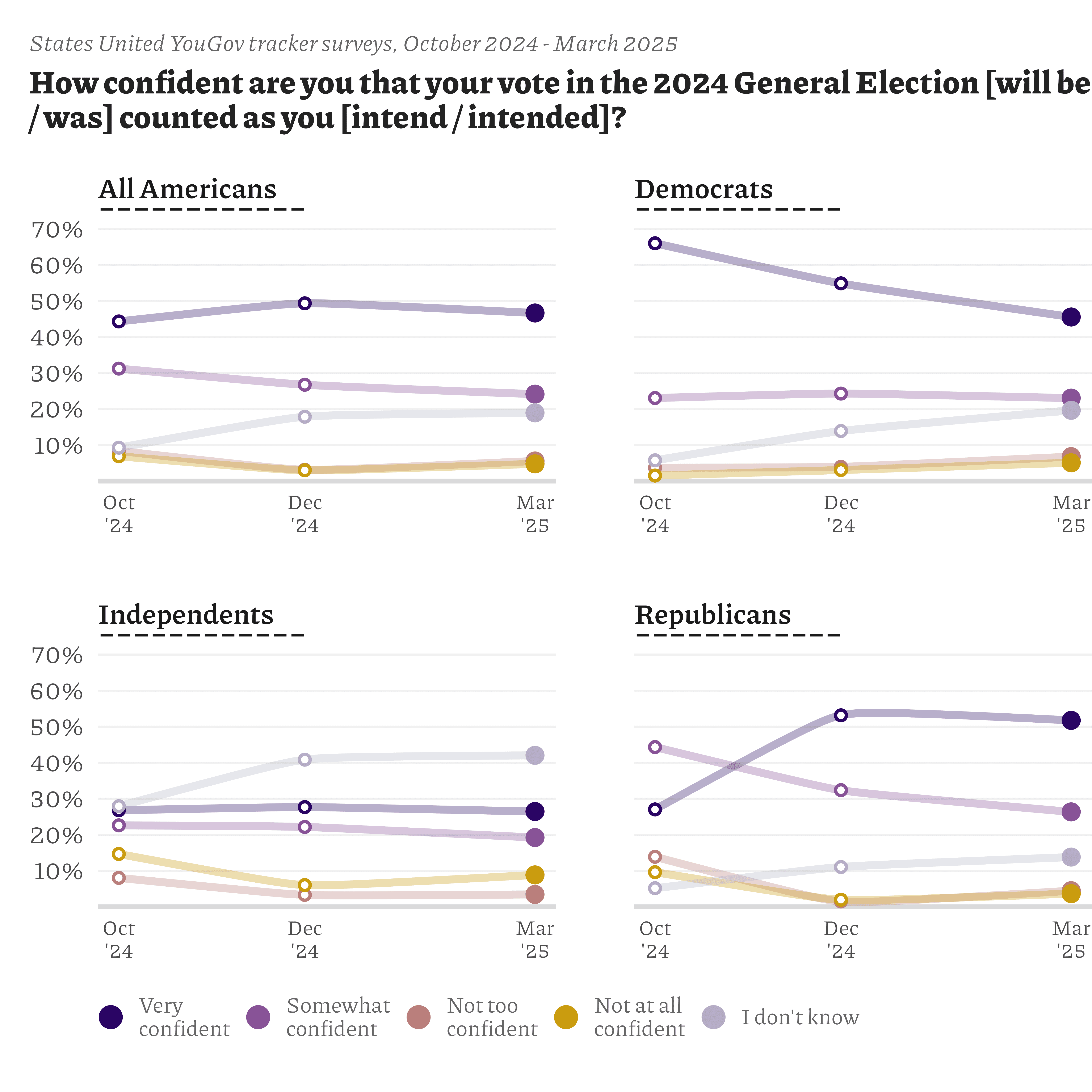

- Americans’ overall confidence that their vote counted as they intended it increased modestly after the 2024 election. In October, the share of Americans who said they were very confident in their 2024 general election vote counting as intended was 43%; this rose to 47% by March 2025.

- Shifts among Republicans accounted for this increase. Prior to Election Day, 27% of Republicans said they were very confident in their vote counting as they intended it; by December this number nearly doubled to 52%; it remained at this level as of March 2025.

- While Americans’ overall confidence increased that their 2024 general election vote counted as intended, such confidence decreased among Democrats. Going into the election, two-thirds of Democrats said that they were very confident their vote would be counted correctly; this confidence declined to 55% after the election, and to 45% by March 2025.

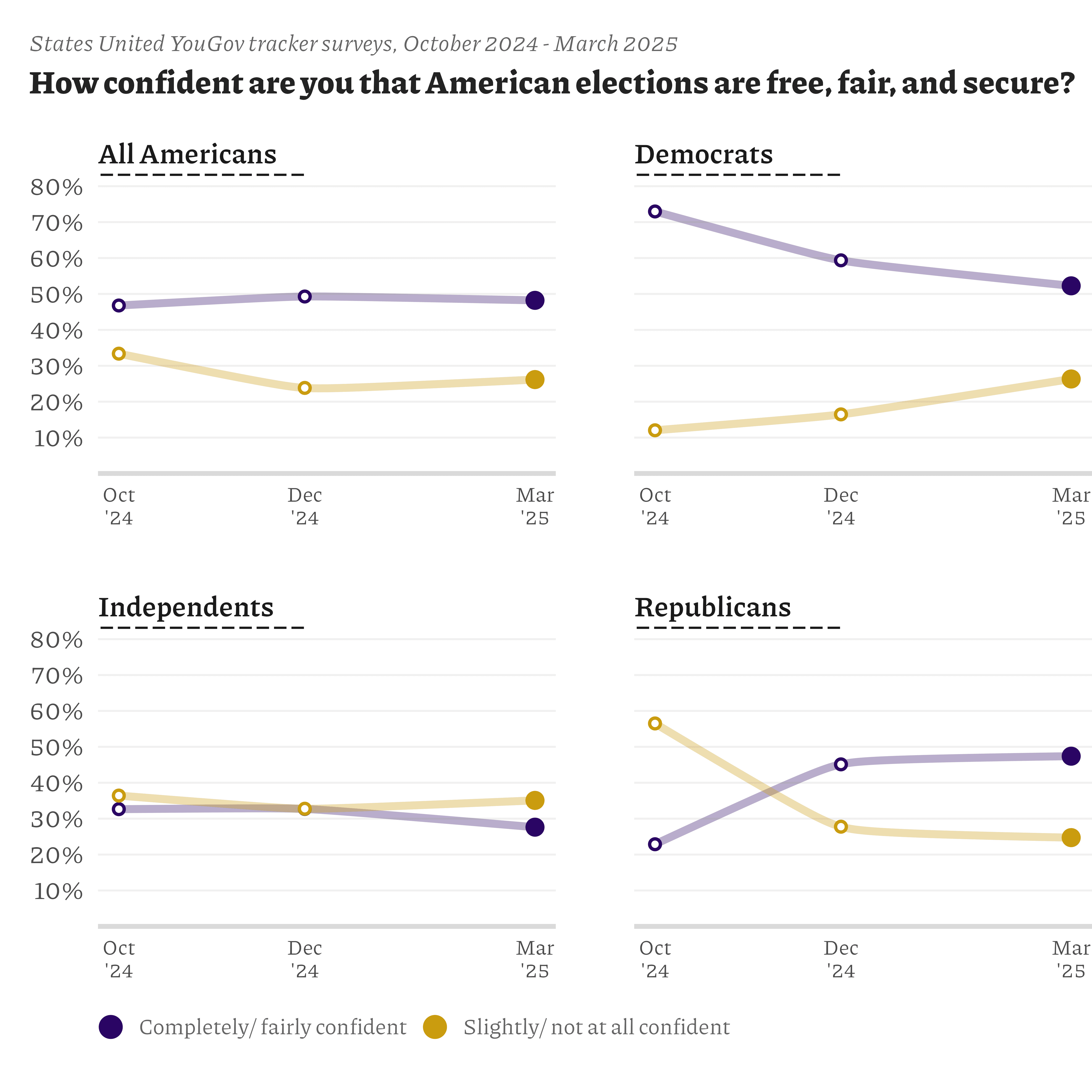

- When asked about whether elections are free, fair, and secure, Americans’ overall confidence similarly rose; it increased among Republicans and declined somewhat among Democrats.

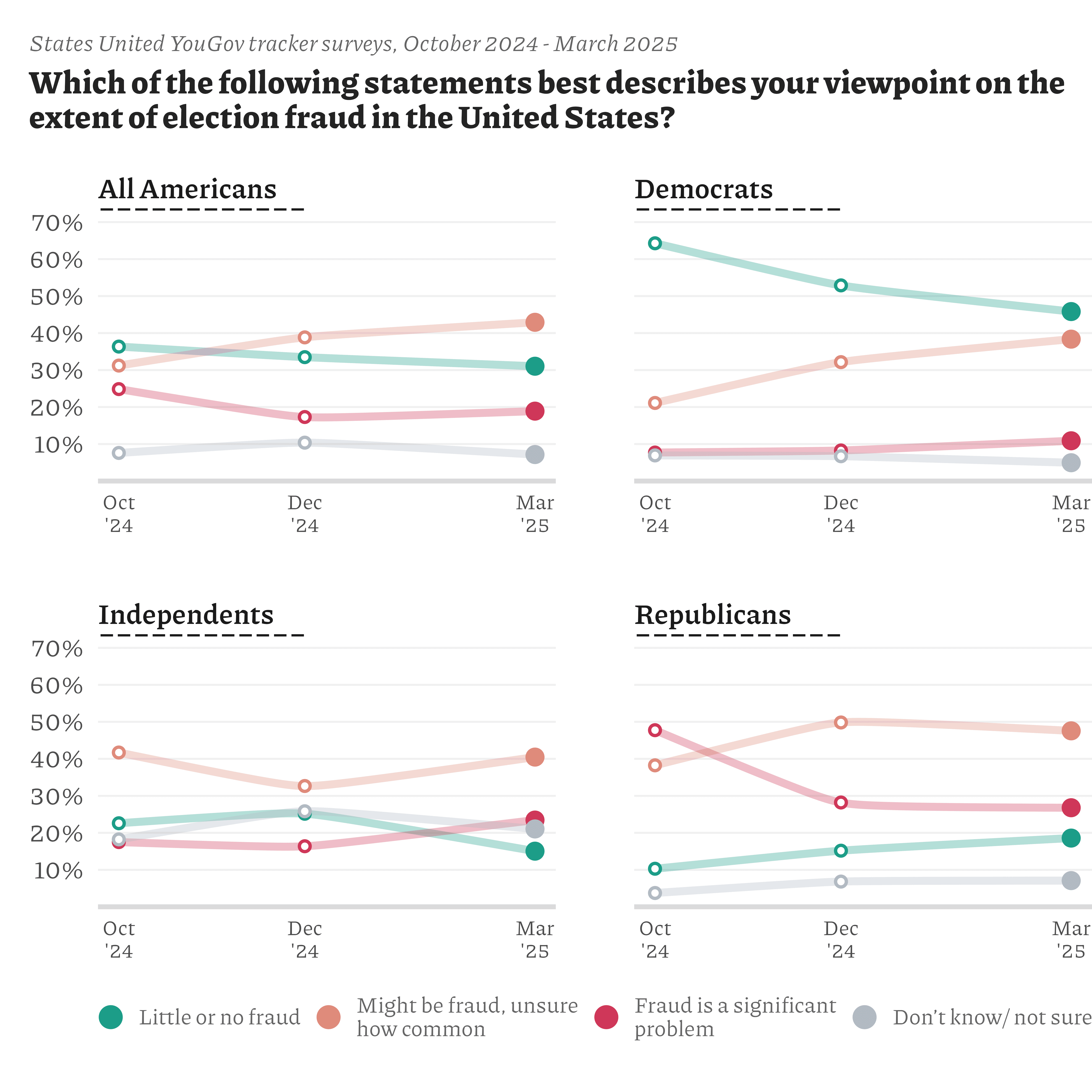

- Concerns about fraud in our elections also shifted: the share of Americans who say fraud is a significant problem in our elections decreased after the election while the share of Americans who say there might be fraud increased. (The former was driven by Republicans, the latter by Democrats.)

- These shifts in confidence coincided with a change in how public officials spoke about the integrity of election results. Claims of fraud or rigging from public officials who had been pushing election denial claims for years were nearly non-existent in the aftermath of the 2024 election—a stark contrast to what they said following the 2020 election. Nevertheless, attacks on the integrity of our election system continue to evolve.

After President Trump won the 2024 election, a notable shift occurred in how the public thinks about fairness in elections. While Democrats showed a dip in election confidence, they nevertheless reported high levels of belief that their vote was counted as intended. Independents showed little change. Where the major shift occurred was among Republicans, who became more assured about the accuracy of the vote after Trump’s victory.

These partisan distinctions highlight a common post-election effect: winning elections drives confidence up, while losing elections pushes confidence down. At the same time, however, this “sore loser/happy winner” effect was more pronounced and enduring than usual after the 2024 election. To what can we attribute this marked shift in confidence?

Concurrent with President Trump’s 2024 victory was a sudden drop-off in claims from public officials casting doubt about the integrity of the 2024 election. Republican leaders, who had been the almost exclusive drivers of election denialism in the lead-up to the 2024 election, stopped voicing these critiques once their preferred candidate won. While attacks on election integrity continue to grow and evolve—from unlawful executive orders to the prolonged election certification battle in North Carolina—the absence of claims questioning the 2024 election’s accuracy likely influenced confidence among the electorate that their vote counted as intended. Because voter attitudes are shaped by messengers they trust, the post-election step back from election denialism among influential public officials—after years of sowing doubt about the 2020 election—was likely reflected in public sentiments that we observed following the election.

While Americans’ confidence in elections shifted in this post-election interval, their views across several other key areas remained mostly unchanged. During this time of political transition, Americans’ high level of support for core principles of our system of government persisted. Since the election, key indicators have remained nearly constant:

- Most Americans continue to agree that it’s more important to count every legal vote than it is for their preferred candidate for president to win.

- Americans have high levels of trust in a variety of methods for voting and for counting votes.

- Views on election denial, political violence, and related matters have generally been stable over the past year. Voters’ attitudes on these issues remain similar to poll findings published by States United in August 2024.

- The coalition of people opposed to political violence continues to be broad and crosses party lines.

The States United Democracy Center partnered with YouGov to conduct the three surveys shown here, which were fielded from October 2024 to March 2025 to gauge Americans’ attitudes.

Responses were additionally weighted to match population characteristics with respect to gender, age, race/ethnicity, education of registered voters, and U.S. Census region based on voter registration lists, the U.S. Census American Community Survey, and the U.S. Census Current Population Survey, as well as 2020 presidential vote.

The margin of error for these surveys ranges from approximately ± 2.7 to 2.8 percentage points, though it is larger for the analysis of partisan subgroups described above. Therefore, sample estimates should differ from their expected value by less than the margin of error in 95% of all samples. This figure does not reflect non-sampling errors, including potential selection bias in panel participation or measurement error.

In keeping with best research practices, we classify independent voters who reported “leaning” toward either the Democratic or Republican parties as partisans. Therefore, we define “independents” as those respondents who professed no partisan attachments whatsoever.