A Democracy Crisis In The Making: August 2022 Edition

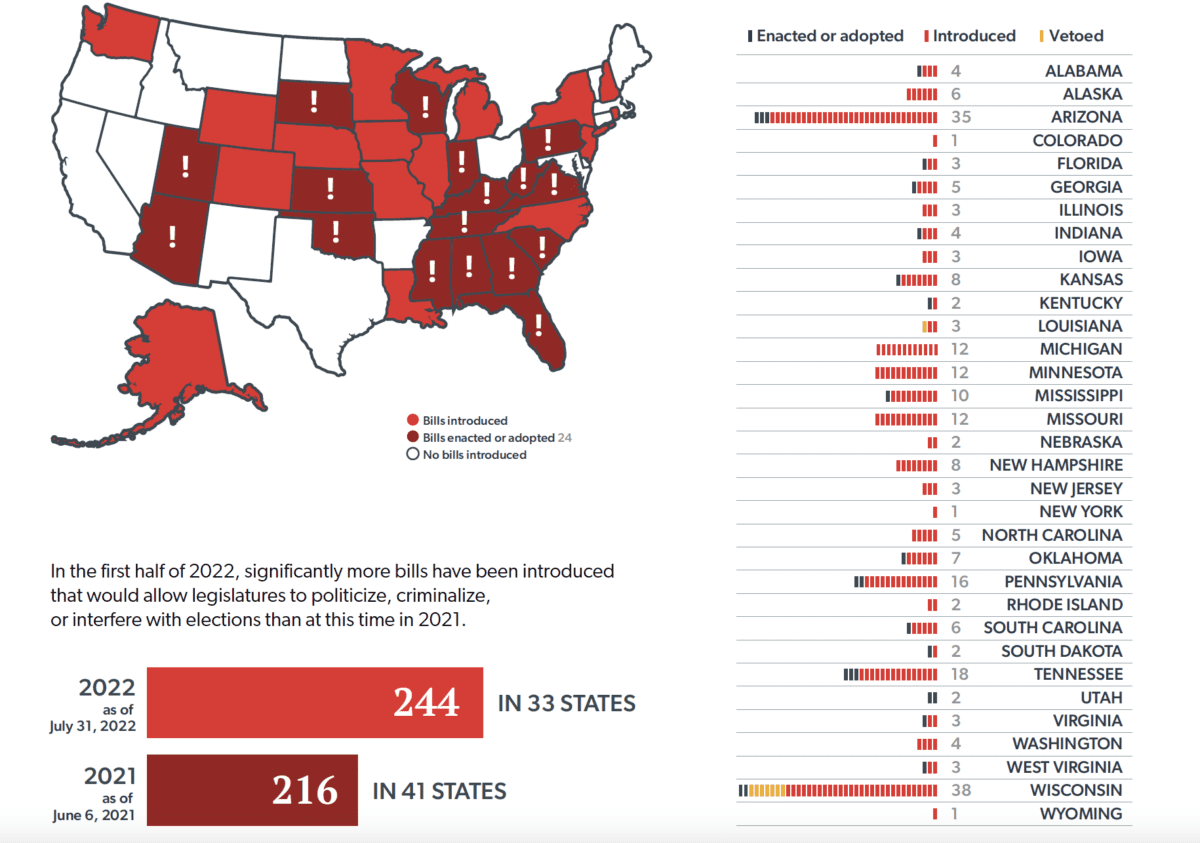

As of July 31, 2022, with most state legislative sessions having drawn to a close, there have been at least 244 bills introduced in 33 states that would interfere with election administration—and 24 of this year’s bills have become law (or have been adopted) across 17 states.

In This Resource

-

Introduction

-

I. Update on Legislative Proposals and Enactments That Increase the Risk of Election Subversion

-

II. Understanding the Independent State Legislature Theory: Moore v. Harper and the Democracy Crisis

-

III. Insider Threats Come Into Sharper Focus

-

Conclusion

-

Note regarding methodology

-

Related Reports

Key Takeaways

- As of July 31, 2022, there have been at least 244 bills introduced in 33 states that would interfere with election administration—and 24 of this year’s bills have become law (or have been adopted) across 17 states.

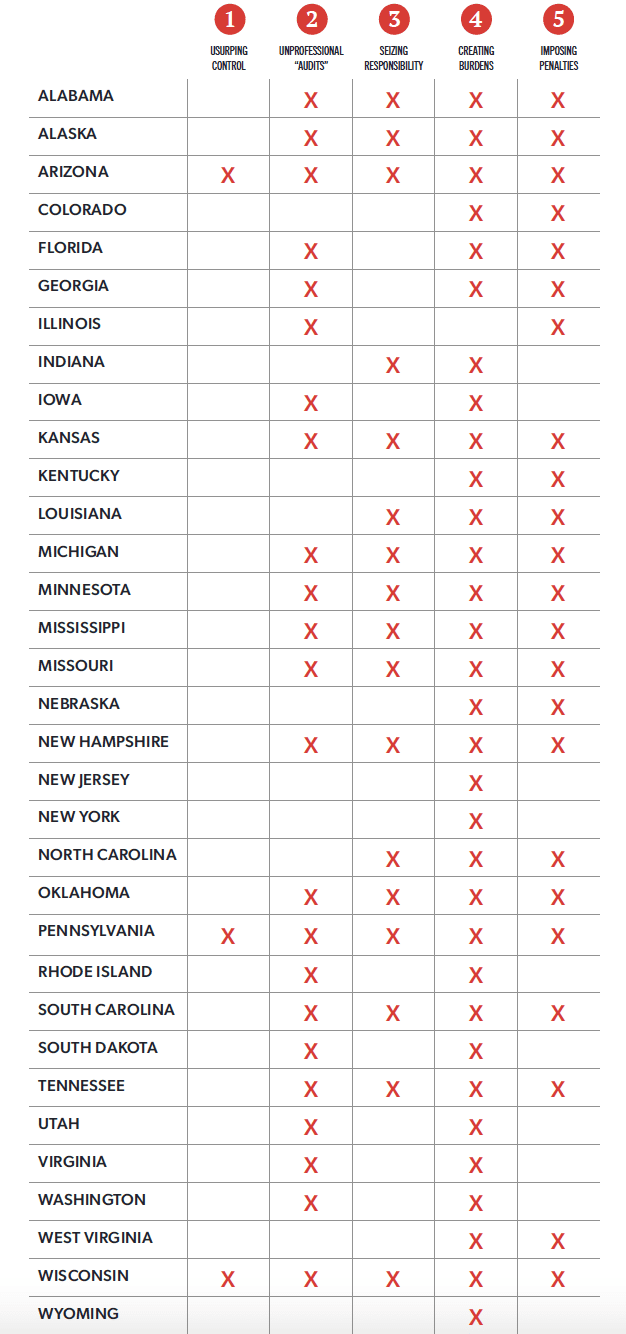

- The five major types of legislative trends that we analyze in this Report are: (1) usurping control over election results; (2) requiring partisan or unprofessional election “audits” or reviews; (3) seizing power over election responsibilities; (4) creating unworkable burdens in election administration; and (5) imposing disproportionate criminal or other penalties.

This report is a partnership between the States United Democracy Center, Law Forward and Protect Democracy.

In the 21 months since the 2020 election, we have seen a breakdown in the longstanding consensus that election administration belongs in the hands of professional, dispassionate experts, and that naked political interference in vote counting is anathema to a functioning democracy. Over the course of 2021 and into 2022, state legislatures have embarked on a sweeping campaign to propose, consider, and, in some cases, enact measures that increase the risk of election subversion—that is, the risk that an election’s declared outcome does not reflect the choice of the voters.

In May, we published the 2022 edition of our ongoing analysis of these efforts. In A Democracy Crisis in the Making: How State Legislatures Are Politicizing, Criminalizing, and Interfering with Election Administration, we identified a pattern across more than 30 states of lawmakers menacing independent and accurate election administration through proposals that, if enacted, would impact practically every step of the electoral process. In the most extreme examples, none of which has been enacted to date, legislators have proposed claiming for themselves the right to reverse election results altogether and to install their own preferred candidates. Other proposals are less overt—bills that would shift power to legislatures to choose and control election officials or that would tie the hands of professional local election administrators. Legislators have also embraced targeting election administrators and election results with unprofessional and biased reviews, designed to sow doubt about the legitimacy of the results. Finally, some of the legislators’ proposals would impose onerous and unrealistic burdens on election administration—for example, a requirement to count all ballots by hand that would introduce errors and delays.

These proposals have a unifying theme: they would make it far easier for hyperpartisan actors to stir up the doubt, chaos, and confusion that could be used as a pretext for election subversion.

They set the stage for a rerun of the democracy subversion playbook of 2020—only this time, if these measures are put in place, anti-democracy players will have more powerful tools at their disposal, and the effort will have a higher chance of success.

As the 2022 general election nears, the integrity and reliability of our voting systems are key campaign issues. For much of the period since the Civil Rights Era, election administration was not an issue for the campaign trail, nor was it one that drove voter choice. Expertly run, accurate, safe, and unbiased elections have been the foundation of our democracy.1For much of American history, and even to this day, the promise of full access to the franchise and free and fair elections has been illusory for many voters. See U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, An Assessment of Minority Voting Rights Access in the United States: 2018 Statutory Enforcement Report, September 2018, usccr.gov/files/pubs/2018/Minority_Voting_Access_2018.pdf. However, in the wake of the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, and during a nearly two-year onslaught of lies and disinformation, public confidence in our voting systems has plummeted. According to one recent poll, about 48 percent of Americans believe it’s likely that elected officials will overturn an election in the coming years simply because their own party did not win.2 Jennifer Agiesta, “CNN Poll: Americans’ confidence in elections has faded since January 6,” CNN, July 21, 2022, https://www.cnn.com/2022/07/21/politics/cnn-pollelections/index.html.

Since the release of our May report, the landscape has only darkened. In this update, we describe three evolving trends—each of them a distinct threat, but connected in the danger they pose to the future of free and fair elections. As we explain in Part I, the number of bills that heighten the risk of election subversion has increased.3To quantify the number of legislative proposals that create a risk of election subversion, we relied on the Voting Rights Lab database and supplemented it with other legislative proposals that we discovered via independent research. We included legislation introduced between December 15, 2021, when our last update stopped, and July 31, 2022. We also included legislation from our 2021 Reports that was still active this year. The States United Democracy Center, Protect Democracy, and Law Forward worked together to analyze each proposal to determine whether it would—if adopted—materially increase the risk of election subversion, and to filter out those that we concluded did not meet that criterion. See Voting Rights Lab, State Voting Rights Tracker, https://tracker.votingrightslab.org. In Part II, we detail a gathering storm cloud as the Supreme Court prepares to consider a case that could rewrite constitutional elections doctrine with an extreme legal theory, upend decades of election law, and accelerate election subversion efforts. Finally, in Part III, we discuss how the insider threat trend—misconduct by officials in trusted election administration roles—has sharpened. With an election less than three months away, it is imperative that these threats be acknowledged and mitigated.

In May, we identified 229 bills of concern—175 introduced in this calendar year alone and 54 that rolled over from the last calendar year—in 33 states. A total of 50 bills had been enacted or adopted, 32 last year and 18 this year. As of July 31, 2022, with most state legislative sessions having drawn to a close, there have been at least 244 bills introduced in 33 states that would interfere with election administration—and 24 of this year’s bills have become law (or have been adopted) across 17 states.4 States United Democracy Center, Democracy Crisis in the Making Report Update: 2021 Year-End Numbers, December 2021, https://statesunited.org/resources/decupdate/#tooltip1.

More here.

In June 2022, the Supreme Court agreed to hear Moore v. Harper, a case from North Carolina that could fundamentally alter the way elections are administered by removing most or all state-level checks on legislatures when they regulate federal elections. It could further empower legislators to enact the policies detailed in our May Report and throw elections into chaos.

In Moore, members of the North Carolina state legislature invoke the radical and erroneous “independent state legislature” (ISL) theory to argue that they were not bound by a state constitutional prohibition on partisan gerrymandering when drawing congressional maps this redistricting cycle.5For more on the legal merits of the theory—or lack thereof—see Helen White, “The Independent State Legislature Theory Should Horrify Supreme Court’s Originalists,” Just Security, June 30, 2022, https://www.justsecurity.org/81990/the-independent-state-legislature-theoryshould-horrify-supreme-courts-originalists/. Proponents of the theory assert that the federal Constitution gives a state legislature the power to regulate federal elections without any checks from other state officials or the constraints of the state’s constitution. Although Moore is a redistricting case, the theory, if adopted, could upend many aspects of election law.

More here.

“Insider threats”—that is, misconduct by officials in trusted election administration roles—continue to pose a risk of election subversion. Although this is a non-legislative form of subversion, it is often driven by the same disinformation that motivates legislative efforts and on some occasions has been openly encouraged by state legislators.6 In Michigan, a criminal investigation into tampering with election equipment uncovered evidence that a state representative was involved in efforts to gain access to the machines. See Christina M. Grossi, letter sent via email to Jocelyn Benson, August 5, 2022, https://www.scribd.com/document/585981221/Letter-to-SOS-Benson-reelection-machine-access-8-5-2022#fullscreen&from_embed. In Pennsylvania, state senator Douglas Mastriano spurred an unauthorized audit in one county while threatening to subpoena it. See Marley Parish, “’An unprecedented situation’: Loose ends remain in Fulton County election review,” Pennsylvania Capital-Star, October 31, 2021, https://www.penncapital-star.com/government-politics/an-unprecedented-situation-looseends-remain-in-fulton-county-election-review/.

Insider threats involve election personnel who engage in misconduct to ensure their preferred candidates win, or because they believe in false conspiracy theories themselves. Multiple instances of insider threats arose during and since the 2020 election. Fortunately, none of these threats have affected election results. However, the three strands of this trend that we noted in our May report continue to grow.

More here.

When we issued the first edition of this Report, in April 2021, we warned of an impending disaster for American democracy. At that time, we called attention to what was then a burgeoning trend—legislation that would unravel centuries of progress toward fair elections and erode the bulwark of nonpartisan election administration.

Almost a year and a half has passed, and our alarm has only increased. The threat from state legislatures has advanced. Dozens of election-interference bills are now written into state law, and many more have been introduced. What’s more, the legislative threat has joined and amplified other efforts to chip away at the simple proposition that election results should reflect the will of the voters.

In recent months, officials in scattered American counties have simply refused to certify valid election results. These attempts have not succeeded so far: they were stopped by a court in New Mexico and are the subject of litigation in Pennsylvania. But they are brazen nonetheless, and amount to a probing of the electoral system for weaknesses. At the same time, politicians who refuse to accept the outcome of the last election are running for statewide jobs that would give them oversight over future elections.

Many have already secured their party’s nomination. Less noticed, a campaign of harassment and threats is driving trusted local election administrators from their jobs. Looking ahead, the Supreme Court is poised to consider a fringe legal theory that would give partisan state legislatures virtually unchecked power over federal elections.

There is yet cause for hope. The vast majority of state legislatures have adjourned for the year, and most of the bills of concern that we identify in this Report have not become law. Some leaders in both parties have openly acknowledged the threat to democracy and stood up against it. We still have a democracy crisis in the making, but committed Americans can come to democracy’s aid and reject efforts to subvert elections.

More here.

Each year, state legislators introduce thousands of bills related to elections. One organization, Voting Rights Lab, currently tracks almost 2,500 election-related bills under consideration by legislatures this year, and that number is likely to rise. To create this Report, we relied on the Voting Rights Lab database and supplemented it with other legislative proposals that we discovered via independent research. We included legislation introduced between December 15, 2021, when our last update stopped, and July 31, 2022. We also included legislation from our 2021 Reports that was still active this year. The States United Democracy Center, Protect Democracy, and Law Forward worked together to analyze each proposal to determine whether it would—if adopted—materially increase the risk of election subversion, and to filter out those that we concluded did not meet that criterion. A complete list of the bills that fall within the scope of this Report is included as an Appendix.

Sources

For much of American history, and even to this day, the promise of full access to the franchise and free and fair elections has been illusory for many voters. See U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, An Assessment of Minority Voting Rights Access in the United States: 2018 Statutory Enforcement Report, September 2018, usccr.gov/files/pubs/2018/Minority_Voting_Access_2018.pdf.

Jennifer Agiesta, “CNN Poll: Americans’ confidence in elections has faded since January 6,” CNN, July 21, 2022, https://www.cnn.com/2022/07/21/politics/cnn-pollelections/index.html.

To quantify the number of legislative proposals that create a risk of election subversion, we relied on the Voting Rights Lab database and supplemented it with other legislative proposals that we discovered via independent research. We included legislation introduced between December 15, 2021, when our last update stopped, and July 31, 2022. We also included legislation from our 2021 Reports that was still active this year. The States United Democracy Center, Protect Democracy, and Law Forward worked together to analyze each proposal to determine whether it would—if adopted—materially increase the risk of election subversion, and to filter out those that we concluded did not meet that criterion. See Voting Rights Lab, State Voting Rights Tracker, https://tracker.votingrightslab.org.

States United Democracy Center, Democracy Crisis in the Making Report Update: 2021 Year-End Numbers, December 2021, https://statesunited.org/resources/decupdate/#tooltip1.

For more on the legal merits of the theory—or lack thereof—see Helen White, “The Independent State Legislature Theory Should Horrify Supreme Court’s Originalists,” Just Security, June 30, 2022, https://www.justsecurity.org/81990/the-independent-state-legislature-theoryshould-horrify-supreme-courts-originalists/.

In Michigan, a criminal investigation into tampering with election equipment uncovered evidence that a state representative was involved in efforts to gain access to the machines. See Christina M. Grossi, letter sent via email to Jocelyn Benson, August 5, 2022, https://www.scribd.com/document/585981221/Letter-to-SOS-Benson-reelection-machine-access-8-5-2022#fullscreen&from_embed. In Pennsylvania, state senator Douglas Mastriano spurred an unauthorized audit in one county while threatening to subpoena it. See Marley Parish, “’An unprecedented situation’: Loose ends remain in Fulton County election review,” Pennsylvania Capital-Star, October 31, 2021, https://www.penncapital-star.com/government-politics/an-unprecedented-situation-looseends-remain-in-fulton-county-election-review/.